Meet the women who are levelling the venture capital playing field

Equal access to funding means the pitch is finally being levelled

Today she is well established—and well known—both as an entrepreneur and as an online “dragon,” evaluating pitches on Next Gen Den, the digital spinoff of CBC TV’s popular Dragons’ Den.

But in 2010, Nicole Verkindt was the one making the pitches. She had launched OMX—a Toronto-based firm that helps companies in a range of industries track and manage the economic impact of their supply-chain decisions—and needed financing. She recalls pitching to more than 100 venture-capital firms and, but for one exception, “we were completely unsuccessful.”

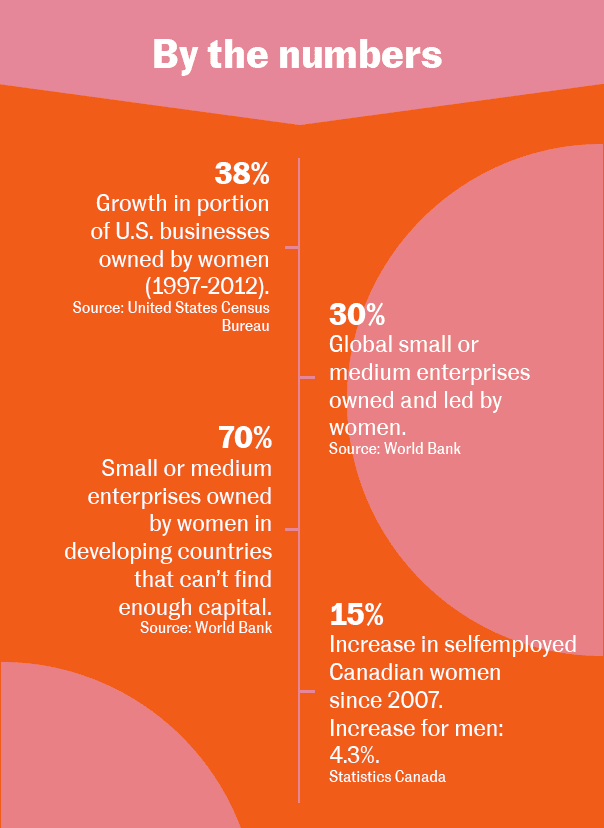

Which is hardly unique. Study after study shows that women-led enterprises comprise a tiny percentage of companies funded by venture capital.

A 2014 report for the Diana Project, an international research effort based at Babson College outside Boston, found that just 2.7% of VC-backed startups had a female CEO.

Investors tend to invest in candidates that mirror themselves

Verkindt attributes her own lack of success to the Catch-22 that Canadian venture-capital firms simply aren’t inclined to back early-stage companies. But she allows that there is also a subconscious bias in VC decision-making: “People tend to want to invest in people that they are comfortable with, that they recognize themselves in.”

“Women are naturally more open and perhaps can be too forthcoming with information during a pitch session,” says Krista Jones, managing director of MaRS Work & Learning. “It’s not that it’s wrong, it’s just different.”

“Women tend to be more realistic,” says Caitlin MacGregor, co-founder and CEO of Plum. “We pound our chests less and we don’t exaggerate as much as men. When I sell my vision to investors, I show that I’m going to be a real business. This is not the same as saying I’m going to be a unicorn. I’m more practical. Maybe too practical.”

Investors tend to ask women more negative questions

These nuances in delivery may feed into a “cycle of bias” that fuels the funding disparity. Researchers reported in the Harvard Business Review last year that they’d found venture capitalists more likely to ask female entrepreneurs negative questions during pitch sessions, perhaps one reason why the male-led startups came away with five times as much money.

In a second report, the researchers found the language that investors used to evaluate proposals made by women was “radically different” from that used for the men’s proposals. Women had their applications dismissed to a far greater extent, and those who did receive support got much less than they wanted.

Often forced to self-finance or “bootstrap” their ventures among friends and family, women have successfully lobbied agencies to create new investment initiatives aimed at levelling the playing field.

Investment options that level the pitch

BDC Capital, the venture capital arm of the Crown-owned Business Development Bank of Canada, has committed $200 million to its Women in Technology Fund—one of the largest of its kind in the world— under the direction of Michelle Scarborough, the company’s managing director of strategic investments. The fund comes, Scarborough says, as more and more women take an interest in building technology enterprises.

As well as BDC, there is a growing number of female-focused crowdfunding platforms, campaigns and investment groups such as iFundWomen, Women You Should Fund and Female Funders, although the funding amounts tend to be small.

“There is a gap in the marketplace,” says Michelle McBane of the MaRS Investment Accelerator Fund in Toronto, “that we are trying to address.”

McBane is the IAF’s senior investment director and was the one who provided some seed money to Verkindt back in 2010. Now, she is also managing director of StandUp Ventures, which MaRS created last year with assistance from BDC, specifically to provide seed-stage support to ventures led by women.

To date, StandUp Ventures has invested in five companies spanning enterprise software and medtech: Bridgit, which helps construction crews manage entire projects from concept to completion; Coconut Software, which enables firms to schedule and track customer appointments; Nudge Rewards, a mobile app that educates and rewards frontline staff, with the goal of improving profits and performance; tealbook, which uses artificial intelligence to help companies manage their supplier contacts more efficiently; and Emovi, makers of an assessment device that helps locate the cause of knee pain.

If you build the fund, entrepreneurs will come

The BDC fund is no less busy. “Our pipeline is bursting at the seams,” says Scarborough, noting that Women in Technology has backed nine companies, as well as leading efforts to invest in other funds, such as StandUp Ventures. The investor goal, she says, is not just to make investments, but to help women-led companies find additional capital and “develop the right skill sets in order to build their businesses for the long term.”

This sort of gender-specific investing has potential pitfalls, according to Verkindt. “I’m not sure how much it helps the case when somebody knows that you only received funding because of your gender.”

On the other hand, she says, “the problem is so bad and the stats are so low that something has to be done for the interim.”

Gender balance is still critical

McBane echoes the notion that it’s important not to “ghettoize” women through such investments, and says she is not looking to create all-female teams. Instead, she works hard to foster diversity in the startups she backs from an early stage, so they can build a culture that is more representative of their customer base, ultimately leading to a greater chance of success.

“Women can’t just raise money from female funds,” she says. “They have to raise money from the entire pool.”

Scarborough agrees. At the end of the day, she says, female entrepreneurs need to find investors best suited to helping their businesses grow. Even so, she would like to see more women VCs, “because there’s some familiarity across the table when you’re pitching.”

Verkindt acknowledges that women are good at getting mentors but says they also have to work harder at getting sponsors, people who can actually do something for them, such as put in a good word for a promotion or provide capital by such-and-such a date.

“You have to go for the ask,” she says. “When you meet with someone, for sure get advice, but say, ‘Who can I talk to that specifically has funding that can do a deal like this?’ ”

McBane, meanwhile, looks forward to the day “when we won’t have female leaders, we’ll just have leaders.”

Mary Gooderham

Mary Gooderham